Sign on the Dotted Line

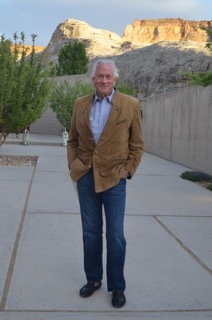

By G. Miki Hayden

Instructor at Writer's Digest University online and private writing coach

firstwriter.com – Saturday December 12, 2020

I just sign blank contracts for books and whatever strikes me as a good idea is what I write about.

~ Roger Zelazny

Contracts seem daunting because the language they are written in is arcane and the contract terms are ones you’ll have to live with, probably a while beyond the life of the book. In this case, fear is a good thing. We should regard the contract with a certain amount of trepidation and not simply sign because we’re drooling with eagerness to be published.

Yes, you’re supposed to rely on your own agent's expertise, but you should know what’s important to you in a contract so you can tell your agent. That’s why you want to find out the basic types of contents that contracts have and what can/should be negotiated and what not.

So even those authors with agents ought to be prepared to read and understand the contract. I said the language is arcane, but it’s not actually that unreadable. Contracts can be dissected by anyone who can write a book. And if you’re going to sign it, you definitely should read it first.

The Boilerplate Contract

The contracts that most writers receive are "boilerplate" contracts. That means the contracts are the standard ones that the publisher issues to just about everyone. A secondary boilerplate form is a contract that the publisher has hashed out specifically with the agency that represents you. Those are the standard contracts with no changes or additions. But all the details of the contract are open to negotiation. You can be creative in requesting changes, but you have to look at the package as a whole.

You won’t be granted everything you’d like unless the publisher wants the book very, very badly, and if the editor wants the book that much, he will express the fact in an offer of a decent amount of money. Along with the money, the editor/publisher might budge on some of the smaller details, though they might hold firm on others. Try to remember the most important thing of all, however, when you finally sign. Whether you’ve received your way on every point or not, if you’re with a reputable imprint, you’re gaining publication and furthering your career.

Your agent may ask you what you want to see in the contract. Such a question might sound as if the agent is abdicating responsibility, but that’s not really what she means. She’ll try to negotiate the best deal possible, but in addition to that, what’s important to you? In signing one contract recently, I wanted to change the prohibition against my using portions of the book elsewhere. I didn’t intend to use pieces of my work in order to compete with this specific book, but rather I would use sections in another work to promote further sales of the first book. So I requested that the clause in the contract be rescinded.

Option Books

I also didn’t want to be obliged to offer the publisher an option book, so I asked to have that clause removed. Be aware that if you do have an option clause in the contract, you want to turn that into a minimal nuisance. You can always say no to any deal involving an option book after you’ve submitted it—but you can also be very specific in the contract that the book offered is within a certain sector of your writing life. For instance, if the book is about cabinet making, but you also write material about dog training, your option book should be restricted to any book about cabinetry.

Further, you’ll want to make sure you have a time limit for the publisher’s review placed in the contract. For instance, you might give the publisher 60 days to make an offer, after which the book offered may be withdrawn. Waiting for a response on an option book is one of the nuisances involved in having an option clause—especially if you’re decided to move on to another publisher after the current book.

Lastly, in regard to the option clause, if you happen to negotiate your own contract, be sure the option says for the next “work” and not “works”; otherwise, you will be contractually obligated to show whatever books follow.

Negotiable Perks

Again, with the whole package in mind, if you haven’t gotten some of the deal you wanted in the contract, you might try for a few sweeteners that the publisher may be willing to grant. Extra comp (complementary) books for the author are certainly one bonus that most of the bigger publishers will be willing to grant in the name of publicity and marketing support. Fifty author copies of the book aren’t unreasonable if you’re with a mainstream press, and you might ask for 100 to 200 advanced reading copies (ARCs). This is a lot and the editor might say no, but then you can explain that you want to send them to reviewers and bookstores, especially where you might be known, or to a group of key readers to generate a buzz.

Along these lines, the publisher might also mail the books for you, if you or your (outside) publicist supply the mailing list. Again, this is what a bigger publisher might do and wouldn’t be the norm with a smaller press (although even small press can be generous with authors’ copies for promotion).

Arranging for certain types of marketing support, even advertising or conference and travel costs to genre events is not unheard of in a contract, although most often, the publisher will simply tell you what you will get and then, not infrequently, renege. If you get the specifics in the contract, you’re more likely to receive the marketing help you’ve been promised.

Also, in the contract, you might ask for a bonus as an additional advance if you sell a certain number of copies within the first year or the book gets on a certain bestseller list. This is considered an additional advance because you don’t have to wait for a royalty check to see the money, which can take a long time.

On the other hand, you don’t want to nickel and dime the publisher at contract time and the house may give you extras anyway. They’ll pay for some ads without your asking, perhaps, make bookmarks or postcards for your book, or will give you overruns of book covers if you ask for them before the print run (these can be used promotionally in various ways). Use a bit of discretion when you negotiate and listen to your agent when she says what you can and should—and what you shouldn’t—request.

Be aware, too, that some publishers are inflexible in their contracts terms, except regarding some of the minor details. Though you can see if you are able to push the envelope, don’t become disagreeable if you can’t. Sometimes we have to accept exactly what’s given.

Verbal Contracts

“I’m flattered by the offer” is about all you can say on the phone or on email when an offer is in the air. Otherwise you’re as good as making a contract without thinking it over or referring it to your agent or attorney. In one case, an author reports she didn’t even know the person saying the publisher wanted to reprint her book was an editor. She knew him as a librarian, but he was, indeed, acting as a contract-making agent of a publisher when he said the house wanted to reprint her earlier novel and what did she think. Wisely, she said she’d have to discuss the matter with her agent. Otherwise, she might have obligated herself to a deal without considering the alternatives. Suppose another imprint wanted the book and wanted to pay more for it at the same time?

A verbal contract works the other way as well. If an editor makes you an offer, that’s a verbal contract, too. That means that even if you don’t see the contract in print until further along in the process (some authors don’t sign the actual contract until the book is nearly ready to be released due to the length of the negotiations and so on), you still have a contract. I’m talking about a mainstream house here, however, as small press can and do behave in oddball ways. While such behavior will catch up with even a small press in short order, I’ve heard stories that would curl your hair and have seen multiple authors caught up in a web of lies and deceit with small press publishers. That’s not inevitable, of course, and many, many small press publishers are honest and above board and would never be anything but.

If an actual offer hasn’t been made, then, of course, the deal can fall apart before the contract stage. That’s why we mostly don’t discuss these things in public until we know the book is sold. Having to say that a sale didn’t work out can be a bit embarrassing.

About the Author

G. Miki Hayden is a short story Edgar winner. She teaches a mystery writing and a thriller writing and other writing classes at Writer's Digest online university. The third edition of her Writing the Mystery is available through Amazon and other good bookshops. She is also the author of The Naked Writer, a comprehensive, easy-to-read style and composition guide for all levels of writers.

Miki's most recent novel out is Respiration, the third book in her Rebirth Series. The New York Times gave her Pacific Empire a rave and listed it on that year's Summer Reading List. Miki is a short story Edgar winner for "The Maids," about the poisoning of French slave holders in Haiti.

"Holder, Oklahoma Senior Police Officer Aaron Clement is out for justice above all, even if he irritates the local hierarchy. Hayden in Dry Bones gives us nothing-barred investigation and plenty of nitty-gritty police procedure—which makes for a real page turner." — Marianna Ramondetta, author of The Barber from Palermo

My Writing Education: A Time Line

My Writing Education: A Time Line The one line that's missing from all the writing advice

The one line that's missing from all the writing advice Getting to know you: 8 questions to ask an interested agent

Getting to know you: 8 questions to ask an interested agent Promotional tips

Promotional tips Avoiding literary agency scams

Avoiding literary agency scams How I got a literary agent - An interview with author Geri Spieler

How I got a literary agent - An interview with author Geri Spieler Author productivity is a publishing problem

Author productivity is a publishing problem What Writing His First Novel Taught Author Ted Bell About Writing His Ninth Novel

What Writing His First Novel Taught Author Ted Bell About Writing His Ninth Novel New Literary Agent Listing: Gabrielle Demblon

New Literary Agent Listing: Gabrielle Demblon Reading Force is delighted to welcome submissions from adults, children and young people to its 2025 Memoir Writing Competition

Reading Force is delighted to welcome submissions from adults, children and young people to its 2025 Memoir Writing Competition New Publisher Listing: Cicada

New Publisher Listing: Cicada Calling all aspiring authors! Here's your chance to win a one-to-one session with a literary agent - plus £1,500

Calling all aspiring authors! Here's your chance to win a one-to-one session with a literary agent - plus £1,500 New prize for translated poetry aims to tap into boom for international-language writing

New prize for translated poetry aims to tap into boom for international-language writing New Literary Agent Listing: Kaylyn Aldridge

New Literary Agent Listing: Kaylyn Aldridge TikTok parent ByteDance is shutting down its short-lived book publisher

TikTok parent ByteDance is shutting down its short-lived book publisher New Magazine Listing: And Other Poems

New Magazine Listing: And Other Poems New Literary Agent Listing: Helen Lane

New Literary Agent Listing: Helen Lane UK audiobook revenue up by almost a third last year

UK audiobook revenue up by almost a third last year New Publisher Listing: Radio Society of Great Britain

New Publisher Listing: Radio Society of Great Britain New Magazine Listing: Emerge Literary Journal

New Magazine Listing: Emerge Literary Journal New Literary Agency Listing: Ghosh Literary

New Literary Agency Listing: Ghosh Literary New Publisher Listing: Hardie Grant

New Publisher Listing: Hardie Grant